Scene 3

(Lights down on EMILY, up on the library of the other house where SUE stands at the mantel playing with her jewelry. AUSTIN enters.)

SUE

(Coldly)

Did you see Mrs. Todd?

AUSTIN

(Very superior)

I told you that I would.

SUE

A woman coveting two men! And you pretend to such discrimination! The imagination beggars!

AUSTIN

Evil to her who evil thinks. Unlike “civic beggars” both of mind and body I recognize value when I see it, and a scientifically trained astronomer with a cultivated, operatically trained lady for his wife greatly enhances the prestige of our little town.

SUE

Yet you – and the Trustees – seem to value David Todd more when he’s out of town or in some other hemisphere altogether, chasing an eclipse! Poor little dud David! He doesn’t realize he’s been eclipsed at home!

AUSTIN

(Consults an extravagant gold watch)

The Trustees of the College are none of your concern.

SUE

And now you want to give Mrs. Todd our property, or so I hear!

AUSTIN

Not your property. Mine and my sisters’; a mere slip of land so the Todds can build a house. The Trustees can’t afford to reward David Todd appropriate to his needs, so I’m helping out.

SUE

But Emily won’t sign.

AUSTIN

(Sighs)

I fear our Poetess knows nothing of business. Nor, I should say, do you. Have you been dosing yourself again?

SUE

(Turns away)

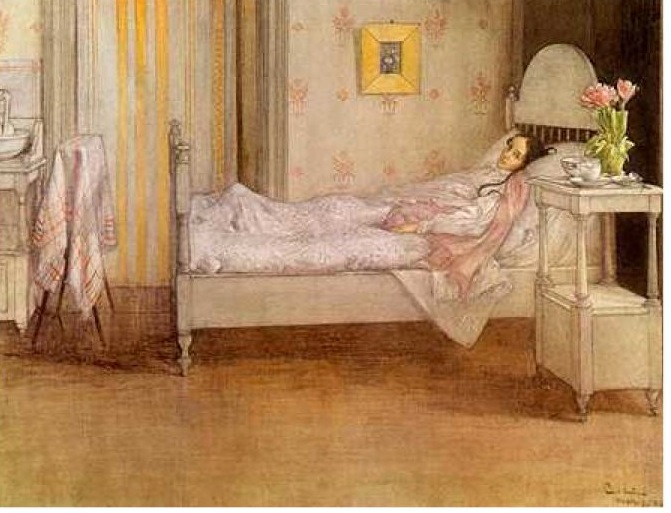

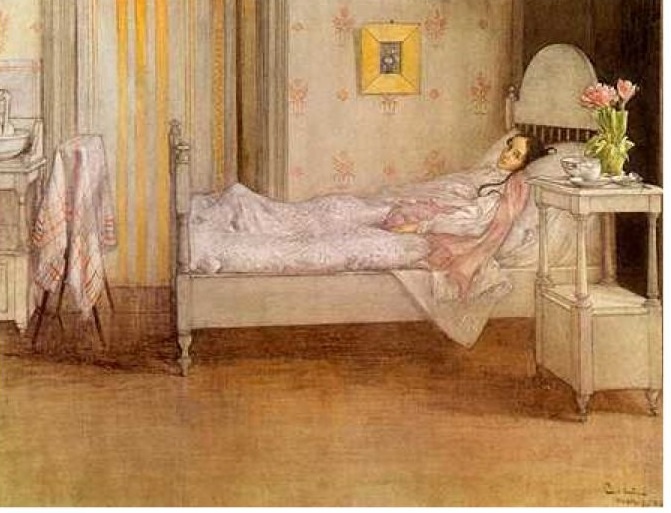

You used to say Emily saw things just as they are! You know I’ve been ill. Your public shamelessness sickens me – and it’s sickening the children.

AUSTIN

Ned was surely sickened by your attempts to destroy him in the womb!

SUE

(Gasps)

Untrue! Your cousin Zebina had the falling sickness his whole life long! While Emily –

AUSTIN

Do not dare to speak of Emily’s illness! Do you deny your morbid fear of childbirth has poisoned our relations?

SUE

You promised me the sacrifice of a marriage blanc! I have your oath written out! Did you forget? “I will ask nothing of you, take nothing from you are not happier in giving me.” I can quote it exactly.

AUSTIN

You entrapped me! You are the spoiler of my life! Did you forget a wife’s duty and a man’s requirements? I went to our wedding as to my own execution!

SUE

(So upset she is tearing the wallpaper in strips from the walls)

You pursued my sister, made her love you and then abandoned her! You broke her heart! I said no a thousand times. Why, oh, why did you have to marry me!

(MAGGIE bursts into the room)

MAGGIE

It’s Emily! Her breathing is that ragged I fear she’s dying!

(They rush to the other house where they gather around a figure lying on the sofa, face turned away, younger sister VINNIE in attendance. We hear the horrible breathing on the sound track. But EMILY, dressed only in a flesh colored leotard, her hair down, watches them with interest from her cross-legged position atop a bookcase. The breathing sound fades.)

EMILY

My cocoon is tightening

I’m feeling for the air

A dim capacity for wings demeans the dress I wear.

This is not death for I stood up

And all the dead lie down.

AUSTIN

(Sobbing)

Sorry for how I teased you, dear sister! Sorry for everything!

EMILY

(Suddenly amazingly youthful again, she is beginning to feel her own body, discovering she can dance, jumps down and advances to address the audience. Her relatives remain absorbed by The Thing on the sofa)

The whole of it came not at once.

Was murder by degrees!

A thrust – and then for Life a chance –

The bliss to cauterize.

SUE

Oh, Emily, don’t leave us! I’m sorry for my temper, for all the times I was self-absorbed, for all the scintillation you elected not to share!

EMILY

(Dancing round SUE)

Susan is a stranger yet;

Those who know her, know her less

The nearer her they get.

To own a Susan of my own

Is of itself a Bliss

Whatever real I forfeit, Lord,

Continue me in this!

(Sister VINNIE kneels, sobbing)

VINNIE

Emily, don’t leave me all alone! First father, then mother, then you!

SUE

(Angrily to AUSTIN)

You won’t need her signature – now!

EMILY

(Dancing)

I felt a funeral in my brain

And mourners to and fro

Kept treading, treading, till it seemed

That sense was breaking through!

And then I heard them lift a box

And creak across my soul –

A plank in reason broke

And I dropped down

Hit a world and

Finished knowing then.

(Spins around)

I feel barefoot all over!

(SUE, AUSTIN and VINNIE rise and face the audience, realizing that death is irreparable)

SUE

Exultation is the going of an inland soul to sea. Past the houses – past the headlands, into deep eternity.

AUSTIN

Like eyes that looked on wastes

So looked the face I looked upon –

VINNIE

So looked itself on me.

(Lights out.)